3.1.1] What causes cancer?

Most cancers are caused by certain mutations (or changes) in the DNA. These in turn are caused by various factors (internal and external) influencing cells.

Cancers not caused directly by mutations may be caused indirectly by viral factors; biomechanical events such as shattered and fragmented chromosomes or the uneven division of genetic material during mitosis. Errors in cell signalling systems can also alter cell division and growth systems but most factors and events can be traced to changes in the DNA.

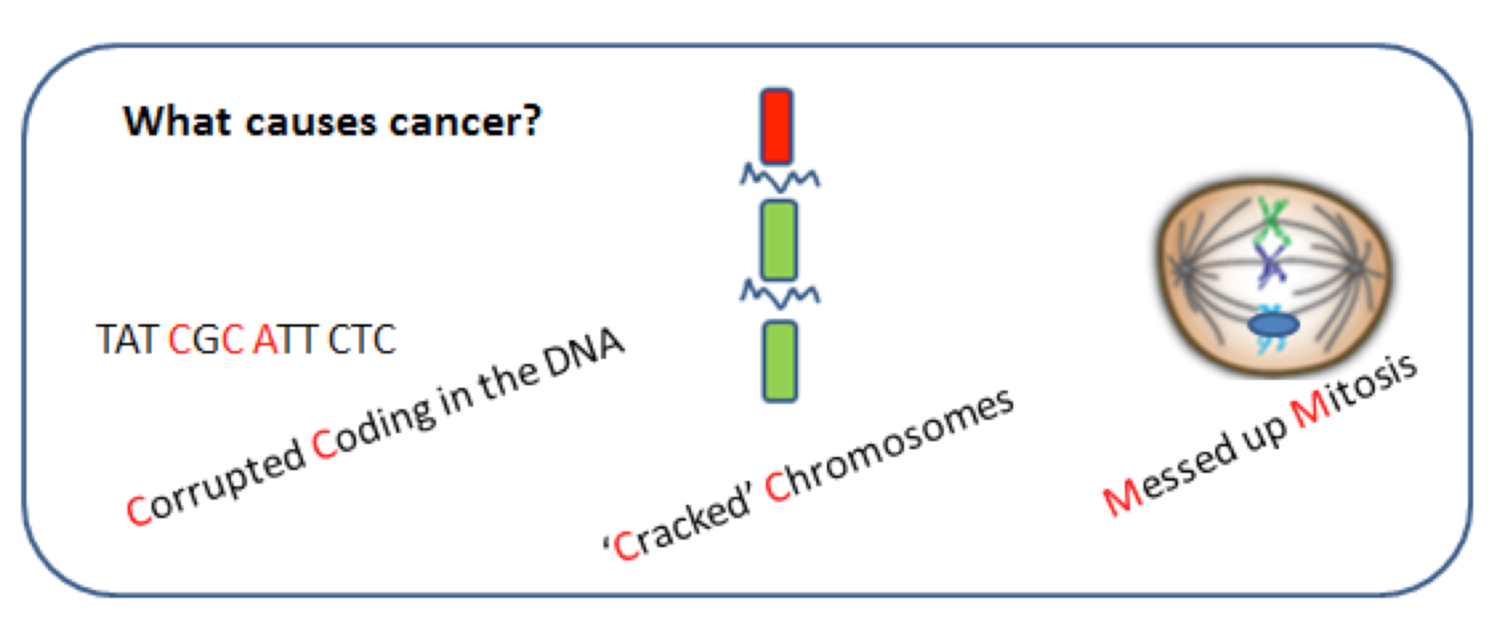

3.1.2] In brief we can say that cells are made to ‘behave badly’ and probably become cancerous by:

- Corrupted Coding, in the DNA, caused by mutations and accounts for most cancers

- ‘Cracked’ (shattered) Chromosomes, causing damage to genes and DNA

- Messed up Mitosis, causing the uneven division of chromosomes

3.1.3] At a basic level cancer may start when the following events happen:

- Mutations cause DNA coding to be modified and when several or more ‘rogue’ mutations accumulate AND the local microenvironment is conducive….

- Inappropriate instructions are made and signalled to protein producing areas resulting in…..

- Protein production being problematic – no proteins or wrong proteins are made, causing ….

- Disorganised and uncontrolled cell growth where cells are not kept under control by apoptosis (programmed cell death)

Rogue mutations that start these critical events are initiated by various factors both internal and external. (See section 4)

3.1.4] Cancer is NOT caused by every mutation, every change in the DNA coding.

Consider the word ‘colour’. Remove the letter ‘u’ and the meaning remains the same. Remove most other letters and the meaning is lost. Whether cells become cancerous depends on many factors.

Mutations or changes to DNA can take place all the time and especially when cells divide.

At birth our genes are those given to us by our parents but even by birth 40-100 spontaneous mutations will have taken place. These are genetic changes but not inherited ones. Some will have affected the genes but only rarely in a medically significant way. Many more mutations will take place during our life-course; most will NOT cause cancer.

3.1.5] Cancer cell derivatives can assist cancer.

Cells in which mutations have caused cancer do not remain static. They continue to divide, mutate and evolve with some mutations causing (1) further chaotic cancer cell growth and, (2) modification of the microenvironment to help sustain growth, mutations and the evolution of the cancer. (See also Section 6).

3.1.6] Investigating the ‘normal’ to learn about what is ‘abnormal’: a classic approach to research.

In 2015 Drs Campbell and Jones and colleagues at The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK, looked at samples of normal human eyelid skin removed from four patients of between 50 and 70 years of age. Small amounts of eyelid tissue were removed to improve the patient’s vision. Eyelid tissue is exposed to sunlight for many years and the researchers wanted to investigate the nature of the mutations in non-cancerous tissue. The researchers estimated that sun-exposed skin would have accumulated within the genome an average of one new mutation for almost every day of life.

From the four patients eyelid tissue 234 biopsies were taken. Genetic sequencing revealed 3760 mutations and a density of 100 cancer-associated mutations per centimetre squared of skin. At the time of the biopsies none of the eyelid tissue was cancerous. About 25% of skin cells carrying at least one cancer associated mutation are found in people without cancer.

So what is the ‘tipping-point of the transition from a cell being cancer associated to cancerous? Are a number of specific mutations required? Or does the microenvironment have to be in a supportive state? Or is it a combination of factors?

A video about this work is available on YouTube. Access by ‘Googling’ ‘What can healthy skin teach us about cancer? Or click here.

End of Level 1. READ MORE at Section 3 level 2, (and section 4: What causes mutations? And Section 10: Reducing the risk.)